J's box

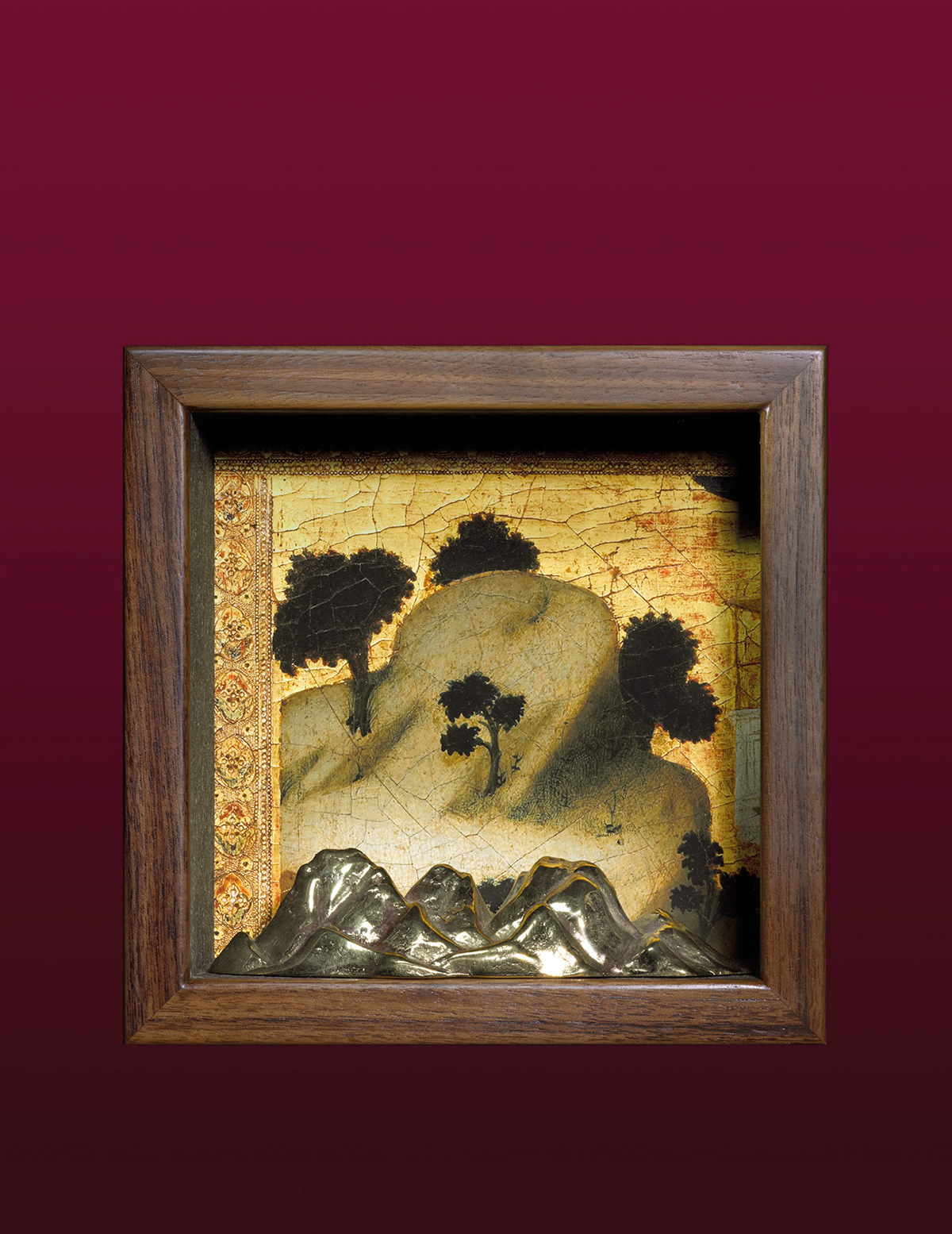

The idea of a box as a means for displaying three-dimensional art is nothing new. Artists such as Picasso, Man Ray, Duchamp and perhaps most notably Joseph Cornell elevated this practice to an art form, often known as assemblage. All of them, particularly Cornell, have had a great influence on me in my decision to take this new direction. I greatly admire the way Cornell, a self-taught and highly innovative artist, was able to combine the present, the immediacy of a moment, with a timeless bond to history and antiquity. He was able to successfully present very accessible creations that were both richly iconographic and often very personal. His art was all about intuition and creating a very special, almost magical, aura. I was also inspired by two, much younger, Chinese artists who were included in my exhibition Parallel Lines in the autumn of 2017. They are Yang Yongliang, who created small, beautifully crafted light-boxes, and Ma Lingli, who made three-dimensional paintings in boxes. Ma Lingli’s effortless ability to combine three-dimensionality with delicate and restrained ink painting has inspired me to focus on the elemental and intuitive connections between things and not be tempted to overcomplicate the works, either visually or intellectually.

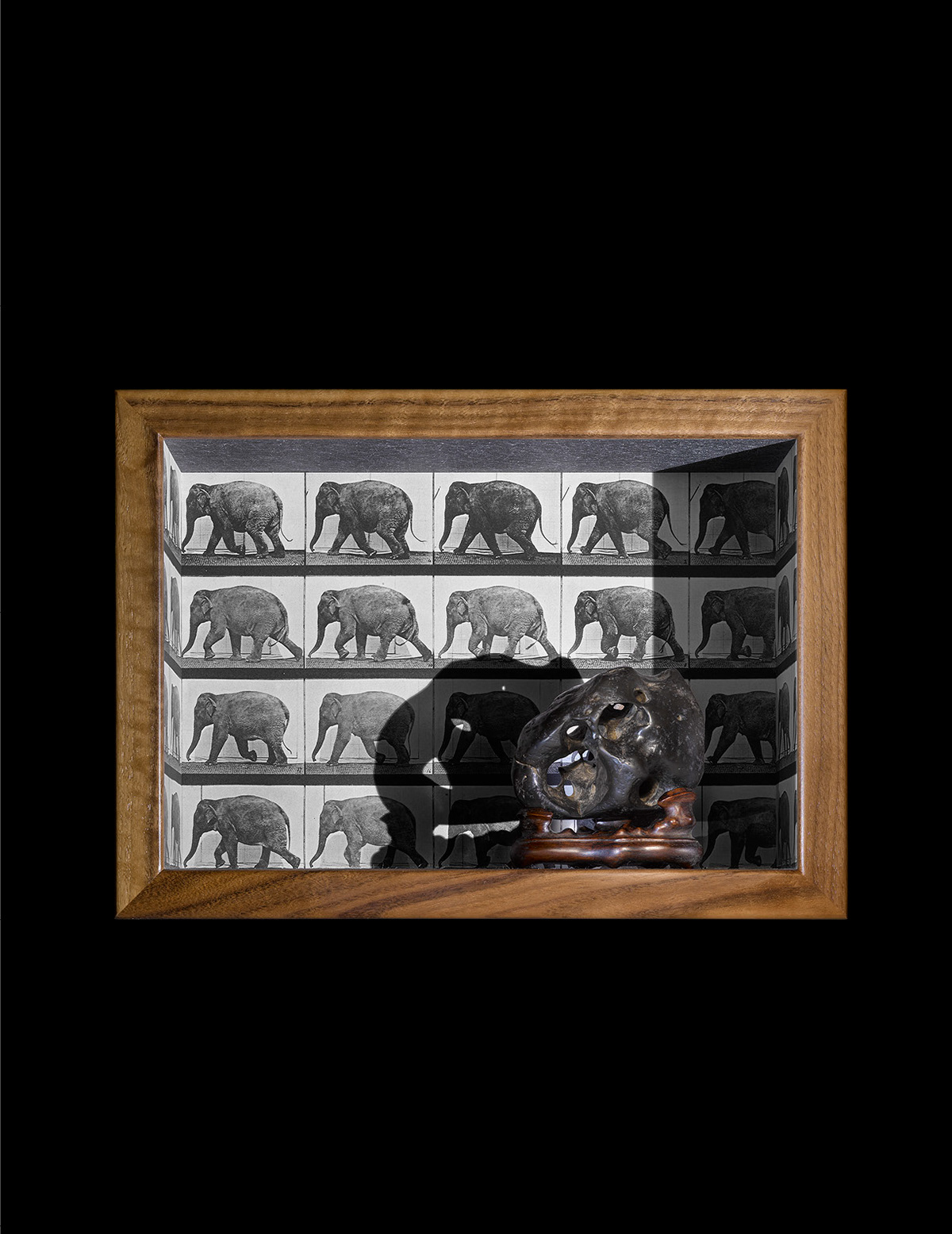

So the idea was devised to create a series of boxes, in two shapes, a square and a rectangle, that could be orientated in either direction. These beautifully crafted yet austere boxes create a perfect space within which to construct a private yet accessible world for each of the small treasures they host. These microcosms are designed to capture the eye and engage the imagination, thus inviting the viewer to connect with the objects. The boxes alone, rather like a frame on a painting, might have been enough to catch the eye, but to stoke the interest and challenge the imagination, a further step was required: to create juxtaposition.

The images used in creating these juxtapositions were carefully sought out. However, the choices are, in the main, instinctive. I felt that if I wanted to instigate an emotive and personal response, I should start with one of my own. The result was a choice of pairings that varies from those more didactically linked to the subject matter to others more indistinct or even abstract. The source materials vary greatly too, but I felt it important that they have a certain gravitas so that they may enhance and react with the objects, rather than merely ornamenting or even detracting from them.

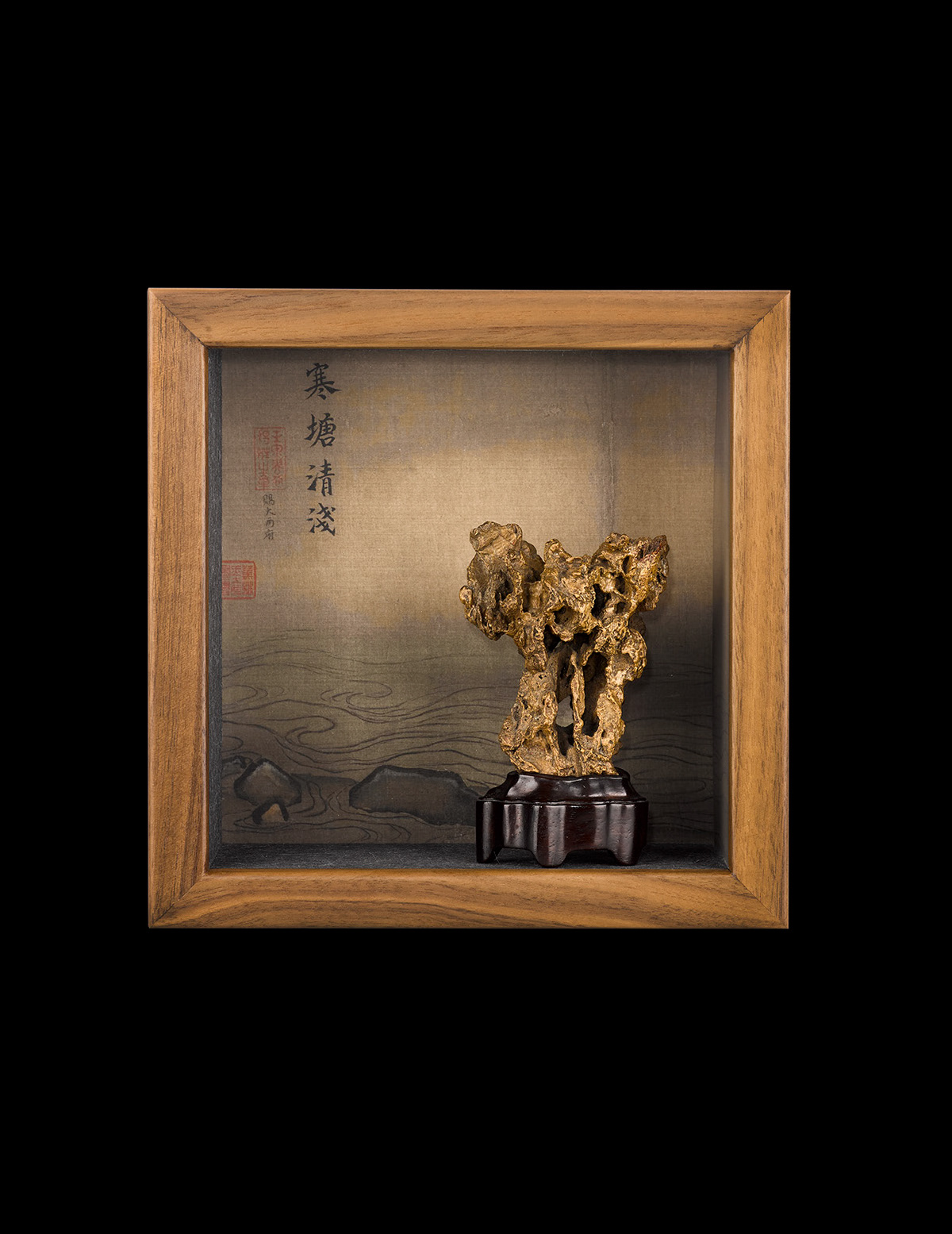

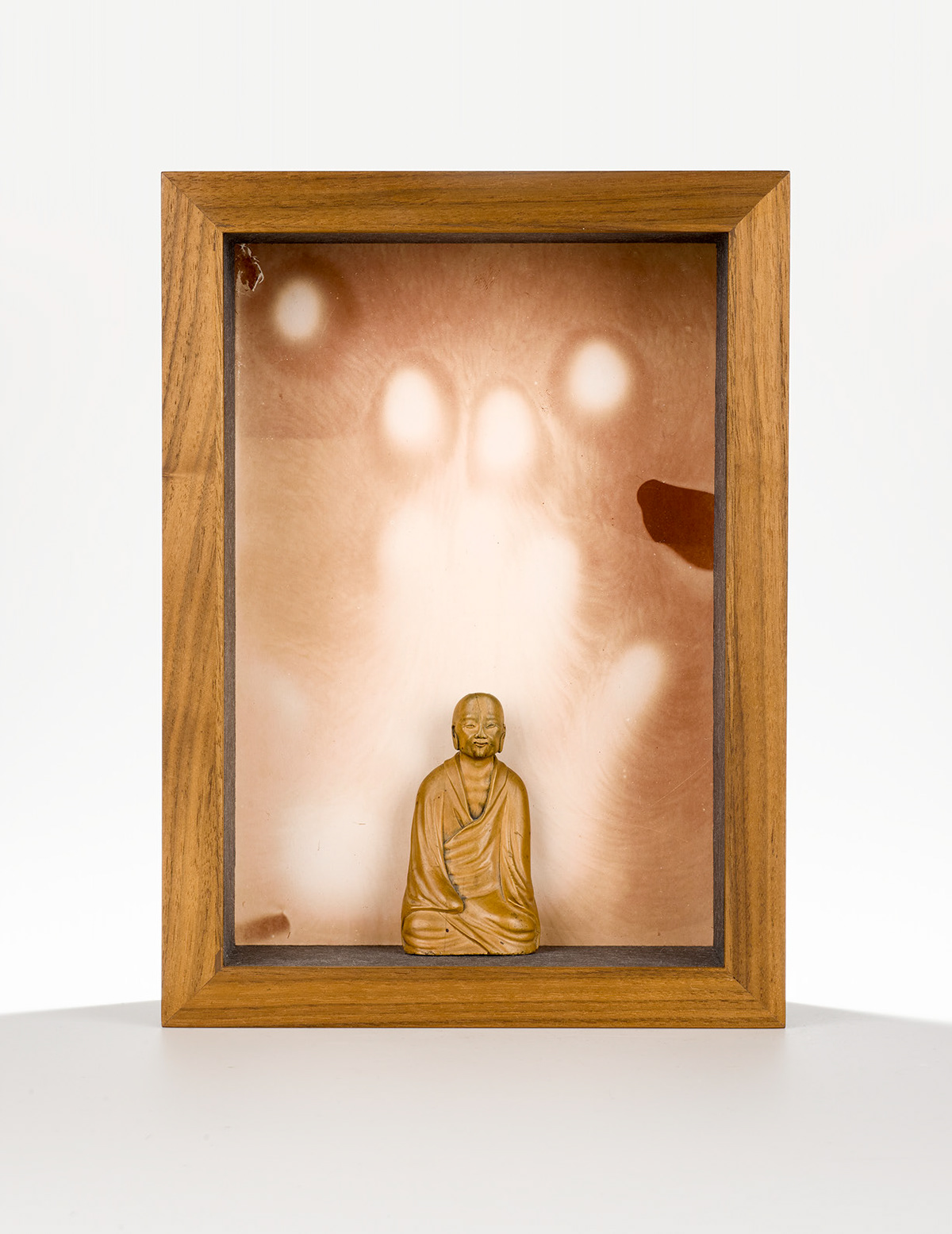

One of the first pairings (box No. 12), one which preceded even the idea of the boxes, was that of the rare lingbi wave-shaped rock and the painting of stormy waves by the Song dynasty artist Ma Yuan (c. 1160‒1225). I have been enamoured with Ma Yuan’s water studies from the moment I first saw them and had for a long time planned a water-themed exhibition inspired by them. To me this is a very natural pairing and the works complement each other in both an aesthetic and an intellectual way. At the more abstract end of the spectrum, perhaps, was my absolute desire to use the Pantheon in Rome as a backdrop for one or more boxes. The Pantheon is, to me, the most spiritual building I have ever set foot in. Its elemental power and simple elegance transcend any of the religious iconography that is housed within. Originally a Roman temple, later converted to a Catholic church, this special space has retained a feeling of spiritual accessibility over the past two millennia. Eventually, I used images of the Pantheon on two boxes. The first (box No. 13) is in conjunction with a wonderful small marble head of a Buddha. Whilst conceptually abstract, I feel that the raw spirituality of both combines to create a powerful vision. The second (box No. 8), perhaps yet more abstract, pairs the geometric lines of the classical architecture with the natural forms of a zitan root sculpture. This is more of a juxtaposition than a complementary pairing and I find the result both beautiful and stimulating.

Thus were born these boxes, limited in number to a total of 88 to maintain their integrity and creative freshness. Each is numbered and accompanied by explanatory text and details. The hope, ambitious though it may be, is not only to show these pieces in a new way and in their dedicated space, but also to ignite a spark in the viewer, encouraging further thought and discourse.

It was only after I had committed to these boxes as an idea that I realized that they were in many ways just an evolution or adjunct to what scholar’s objects were designed for in the first place. The Chinese scholar, often stuck in the drudgery of his mundane and often urban existence, yearned for an escape. In the comfort and privacy of his studio, surrounded by his books, furniture and objects, he longed for an ascent to a higher, more rewarding plane. Using the rituals of tea making, incense, music, and preparation of ink for painting and calligraphy, he would attempt to enter a meditative and creative space, free of the baggage of the ‘dusty world’. Coming to his aid were his rocks and brushrests, whose fantastic shapes transported him to lofty peaks, and his brushpots and boxes, whose natural grain patterns brought him into closer synchronicity with the natural life force, or qi, that flowed through all things.

These objects helped empty his mind so that it was free to wander, but also helped him see. To see the objects, their beauty and beyond. They helped him embark on the journey to a higher plane, and then back again. So it might be with these boxes, whose objects and juxtaposed images may aid us to better see their true beauty and begin a journey of our own.